Information for patients

Living with breathlessness

This is a guide for those who experience shortness of breath. It may also be useful to people close to them.

You will find practical advice and suggestions to help you to cope with breathlessness.

How your lungs work

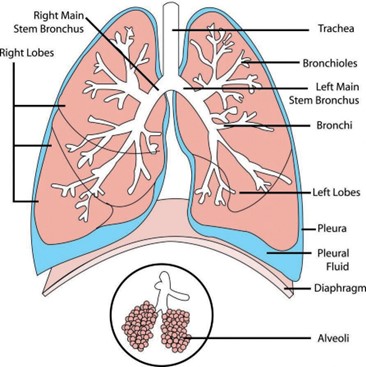

Oxygen is a gas in the air that the body needs to function. The lungs are the organs that take oxygen into the body.

Lungs are located in the chest, one either side of the heart. The inside of the lung looks like a giant sponge with a mass of fine tubes, the smallest of which end in tiny air sacs called alveoli. When you breathe in, the air flows through your mouth or nose and down the series of tubes until it reaches the alveoli, where the oxygen enters the blood through tiny vessels called capillaries.

Carbon dioxide (CO2), a waste product from the cells, is passed out of the blood and is breathed out when you exhale. There are 300 million alveoli with a wrinkled surface in order to provide a large surface area for oxygen absorption.

Under the lungs is a large muscular sheet, called the diaphragm, which separates the chest cavity from the abdomen. The diaphragm is the main muscle of respiration and assists the movement of air in and out of the lungs.

Approximately 10,000 litres of air moves in and out of the lungs every day but most of the time, we are not even aware that our lungs are working. However, when the lungs work less efficiently, due to damage or disease, we can become aware of a number of different sensations, one of which is shortness of breath.

Natural responses

You may have found that when you feel short of breath you ‘naturally’ do one or more of the following, increasing the feeling of being breathless:

Use your shoulders and upper chest muscles

We usually use the diaphragm and lower chest muscles to breathe. In heavy exercise the muscles of the upper chest and shoulders can help, but these muscles are not designed to work for long periods of time and get tired easily. If overworked, the muscles become tense, work less efficiently and use more oxygen – adding to the sense of breathlessness.

Increase the rate of breathing

Taking rapid shallow breaths. This is inefficient because it takes more effort and therefore more energy to bring air in quickly (think of trying to blow up a balloon quickly rather than gently).

Also, described in the section on how the lungs work, oxygen is not available to the body until it reaches the alveoli (air sacs). If the air only flows through the passages and not to the sacs, the body cannot use the oxygen that is brought in.

Breathe deeply

Concentrating on trying to take a deep breath in, does not allow for air already ‘used’ to be breathed out, a bit like trying to refill a jug of water without emptying it first! Deep breathing also increases use of the upper chest and uses more energy.

Feelings of fear, anxiety, frustration, anger, panic and unrest

Common responses when feeling short of breath. They are a protective action by your body similar to when something causes you pain. The emotional reactions can have a direct effect of increasing the rate of breathing as well as alerting your body (as when you are startled) which includes tensing muscles.

People have said that knowing others experience similar fears, anxieties and concerns can be reassuring.

SLOW, RELAXED BREATHS ARE BEST.

The following sections comprise of some suggestions that may help you achieve this.

Positioning

As you ease yourself into this position ensure you have something secure to hold onto such as a table or chair. This will provide extra support and give you something to push against as you stand up. Also having something to lean back against once in that position is helpful. If you need to work at a level below your waist, emptying the washing machine or a cupboard, or gardening, use a low stool and sit, rather than bend.

When you feel short of breath, find a position that supports the shoulders, relaxes the upper chest and allows the abdomen and diaphragm to expand. The following are suggestions, but if you find another position more helpful, use it. The objective is to find something that suits you, increasing the flow of air into your lungs.

Sitting leaning forwards

Sit on a chair and lean forwards with your arms resting on your thighs, with your wrists relaxed. Alternatively, you may prefer sitting back with your arms relaxed, resting on your thighs with palms facing upwards.

Standing leaning forwards

Stand leaning forwards, with your arms resting on a ledge, eg windowsill, bench or banister rail. Alternatively, lean back against a wall, with your shoulders relaxed and arms resting down by your side. Your feet slightly apart and about 30cm (12”) from the wall.

Gentle breathing

In a comfortable position, try gentle, relaxed breathing. Place your hand on your tummy just below the ribs. Gently sigh out, allowing the tummy to ‘shrink’.

Then, ‘allow’ the air in, feeling your tummy expand slightly (like filling a balloon).

Focus on where the breathing is happening, a feeling of breathing around the waist. If you find this difficult, try watching the movement in a mirror or try putting a light object on your tummy (an empty yoghurt pot is ideal) and watch how it moves with your breathing.

As you breathe out, imagine that you are making a candle flame flicker; feel your shoulders and upper chest relax. Try making the breath out twice as long as the breath in, counting may help. Sigh out, pause, then allow the air in.

This method of breathing is useful to regain control when feeling breathless. If you practise abdominal breathing initially when you are relaxed and not breathless, you will become familiar with the process, and it will be easier to adopt this pattern when you need it.

Gentle breathing and positioning alone can help some people feel more in control. In addition, it may be beneficial to relax your mind as well as your upper chest and shoulders. To do this, continue with your breathing control and add in one of the following suggestions.

These are some of the ways in which people we have worked with have described their experience of living with and managing breathlessness.

Relaxation

Learning to relax can be helpful in reducing anxiety and managing the experience of breathlessness. There is no right or wrong technique but as any new skill practice is essential to master it. Try to set aside 20-30 minutes each day:

- Find a quiet place and make yourself comfortable, you may want to listen to some relaxing music, it may be easier to relax with your eyes closed

- When comfortable breathe in and out gently at your own pace, don’t force your breathing

- As you breathe out allow your shoulders to drop, and imagine a feeling of calm; continue calm gentle breathing

- As you breathe gently imagine your muscles relaxing

- While doing this you may like to imagine yourself in a pleasant place where you can feel even more relaxed.

Does anyone else feel like this?

Many people have told us that knowing others experience similar fears, anxieties and concerns can be very reassuring. These are some of the ways in which people we have worked with have described their experience of living with and managing breathlessness.

If I could just control these attacks of breathlessness I'd be ok – I ask myself, is this my last day?"

I feel like I can do things but then I try and I lose my energy."

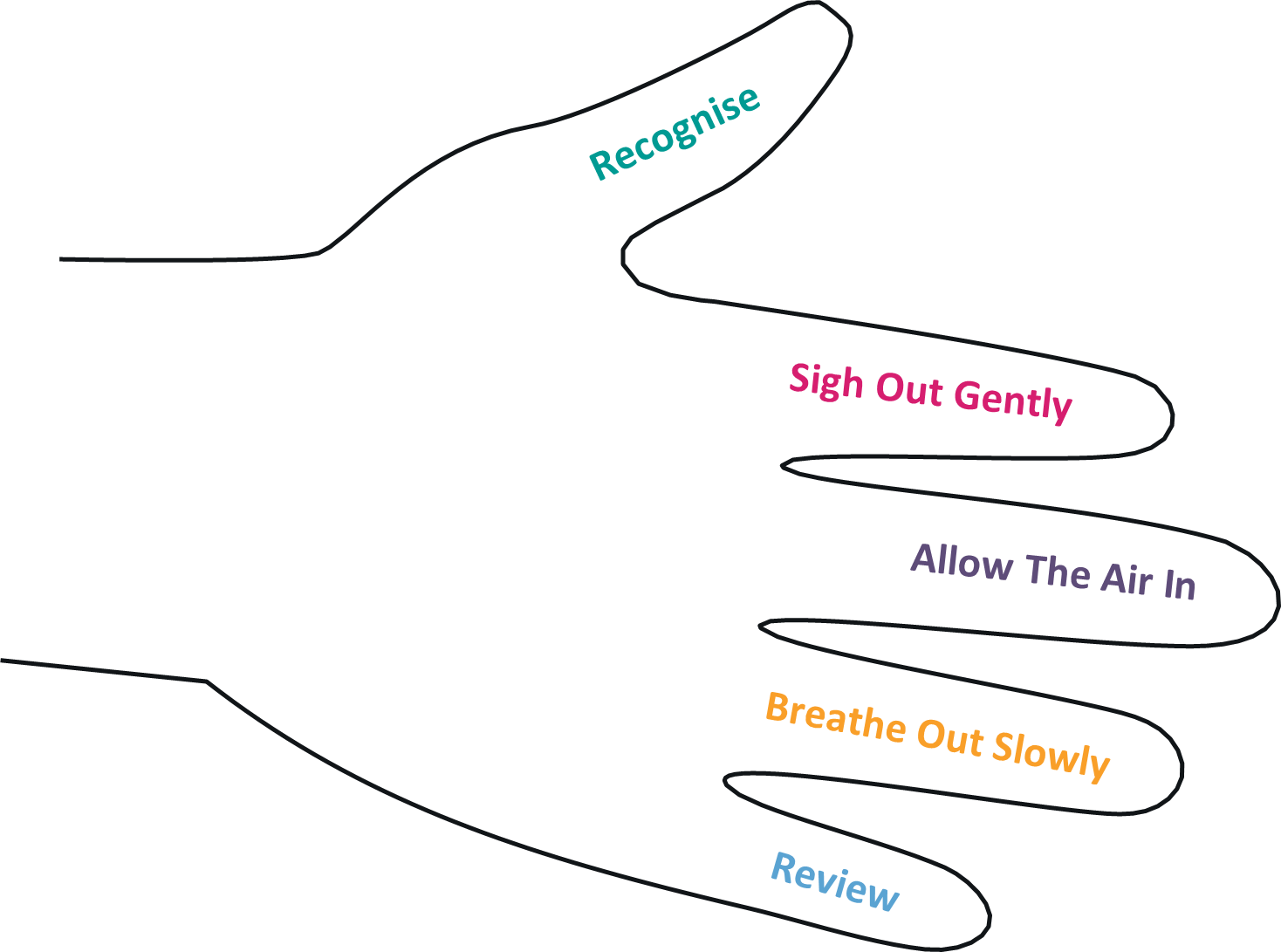

The calming hand

When you are short of breath it can make you worried. This in turn can make you more breathless and may make you feel a sense of panic.

You may find that this routine helps:

Place your left hand in your lap or on the arm of a chair with your palm facing up. Always start with your thumb, grasp each finger in turn, follow the instructions below:

Thumb: Recognise your signs of panic and the need to use the hand.

First finger: Sigh out gently to help relax your neck and shoulder muscles.

Second finger: Allow the air in, breathing around the waist.

Ring finger: Breathe out slowly and try to make the breath out slightly longer than the breath in.

Little finger: Review and if in control, stretch out your fingers until you feel the tension build in the arms, then STOP, let the hand drop, feel the tension go and your shoulders relax.

If not in control start the exercise again.

10 point plan to help you cope

- Position yourself comfortably

- Have cool air on your face – use a fan or open a window

- Take sips of cold water or sharp fruit Suck small pieces of mint or lozenge – these may make your throat feel clearer

- Practise relaxed, gentle If in doubt, sigh out

- Listen to music you find relaxing or a relaxation tape or watch TV

- Wear loose clothing

- Relaxing massage for the neck and shoulders can be helpful, possibly using appropriate aromatherapy oil

- Use the ‘calming hand’ or whatever else helps when you start to feel anxious or panicky

- When walking, try breathing out for 2 steps and in for 1, or out for 3 and in for 2. Or, simply repeat to yourself, ‘breathe out’, ‘let go’. When walking on slopes or up stairs remember not to hold your breath. Try to breathe rhythmically in time with your steps.

- Try to let your muscles breathe with you rather than against

These are some of the ways in which people we have worked with have described their experience of living with and managing breathlessness.

Feedback – we welcome your compliments and complaints

We are keen to develop and improve our services and welcome positive and negative feedback, including any concerns you may have. You can:

- Speak to any member of the team either in person or over the phone by calling our 24-hour adviceline on 01823 333822 or 01935 709480

- Email us at [email protected] or through our website

- Formal complaints should be addressed to the Chief Executive